SMS Pillau

Pillau, c. 1914–16 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

German Empire German Empire | |

| Name | Pillau |

| Namesake | Pillau |

| Builder | Schichau, Danzig |

| Laid down | 12 April 1913 |

| Launched | 11 April 1914 |

| Commissioned | 14 December 1914 |

| Stricken | 5 November 1919 |

| Fate | Ceded to Italy 20 July 1920 |

Italy Italy | |

| Name | Bari |

| Namesake | Bari |

| Acquired | 20 July 1920 |

| Commissioned | 21 January 1924 |

| Fate | Sunk 28 June 1943, scrapped 1948 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Pillau-class light cruiser |

| Displacement |

|

| Length | 135.3 m (444 ft) |

| Beam | 13.6 m (45 ft) |

| Draft | 5.98 m (19.6 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h) |

| Range | 4,300 nmi (8,000 km; 4,900 mi) at 12 kn (22 km/h; 14 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

SMS Pillau was a light cruiser of the Imperial German Navy. The ship, originally ordered in 1913 by the Russian navy under the name Maraviev Amurskyy, was launched in April 1914 at the Schichau-Werke shipyard in Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland). However, due to the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, the incomplete ship was confiscated by Germany and renamed SMS Pillau for the East Prussian port of Pillau (now Baltiysk, Russia). Pillau was commissioned into the German Navy in December 1914. She was armed with a main battery of eight 15 cm SK L/45 (5.9-inch) guns and had a top speed of 27.5 kn (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). One sister ship was built, Elbing.

Pillau spent the majority of her career in II Scouting Group, and saw service in both the Baltic and North Seas. In August 1915, she participated in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga against the Russian Navy, and on 31 May – 1 June 1916, she saw significant action at the Battle of Jutland. She was hit by a large-caliber shell once in the engagement, but suffered only moderate damage. She assisted the badly damaged battlecruiser SMS Seydlitz reach port on 2 June after the conclusion of the battle. She also took part in the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight, though was not damaged in the engagement. Pillau was assigned to the planned, final operation of the High Seas Fleet in the closing weeks of the war, but a large scale mutiny forced it to be canceled.

After the end of the war, Pillau was ceded to Italy as a war prize in 1920. Renamed Bari, she was commissioned in the Regia Marina (Royal Navy) in January 1924. She was modified and rebuilt several times over the next two decades. In the early years of World War II, she provided gunfire support to Italian troops in several engagements in the Mediterranean. In 1943, she was slated to become an anti-aircraft defense ship, but while awaiting conversion, she was sunk by USAAF bombers in Livorno in June 1943. The wreck was partially scrapped by the Germans in 1944, and ultimately raised for scrapping in January 1948.

Design

In 1912, the Imperial Russian Navy held a design competition for a new class of cruisers intended for service in their colonial empire, which were to replace the ageing Askold and Zhemchug in East Asian waters. Several foreign firms, including the German company Schichau-Werke, submitted proposals for the vessels. The Russian fleet was in dire need of new cruisers, and only Schichau promised to meet an early delivery deadline, so they received the contracts for two ships in December 1912.[1]

Pillau was 135.3 meters (444 ft) long overall and had a beam of 13.6 m (45 ft) and a draft of 5.98 m (19.6 ft) forward. She displaced 5,252 t (5,169 long tons) at full load. Her propulsion system consisted of two sets of Marine steam turbines driving two 3.5-meter (11 ft) propellers. They were designed to give 30,000 shaft horsepower (22,000 kW). These were powered by six coal-fired Yarrow water-tube boilers, and four oil-fired Yarrow boilers. These gave the ship a top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). Pillau carried 620 t (610 long tons) of coal, and an additional 580 t (570 long tons) of oil that gave her a range of approximately 4,300 nautical miles (8,000 km; 4,900 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph). Pillau had a crew of twenty-one officers and 421 enlisted men.[2]

The ship was armed with eight 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, four were located amidships, two on either side, and two were side by side aft.[3] She also carried four 5.2 cm (2 in) SK L/55 anti-aircraft guns, though these were replaced with a pair of two 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 anti-aircraft guns. She was also equipped with a pair of 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes mounted on the deck. She could also carry 120 mines. The conning tower had 75 mm (3 in) thick sides, and the deck was covered with up to 80 mm (3.1 in) thick armor plate.[4]

Service history

German service

Pillau was ordered by the Imperial Russian Navy as Maraviev Amurskyy from the Schichau-Werke shipyard in Danzig. She was laid down on 12 April 1913, and was launched on 11 April 1914, after which fitting-out work commenced. Following the start of World War I, which saw Germany and Russia on opposite sides of the conflict, the German government seized the ship on 5 August, which was already nearing completion. She was renamed Pillau after the town of that name. She was commissioned into service on 14 December to begin sea trials, under the command of Fregattenkapitän (FK—Frigate Captain) Lebrecht von Klitzing. In January 1915, Klitzing was replaced by FK Konrad Mommsen. Pillau's initial testing was completed on 13 March 1915.[2][5][6]

Following her commissioning, Pillau was assigned to II Scouting Group. Her first major operation took place on 17–18 April, which was a sweep by the ships of II Scouting Group in the direction of Swarte Bank. Another operation, this time with the entire High Seas Fleet, took place from 21 to 22 April. Neither operation resulted in contact with vessels of the British Royal Navy. On 17 May, Pillau and the rest of her group sortied for a minelaying operation in the North Sea that lasted into the following day. She next went to sea on 29 May, again with the High Seas Fleet, for another unsuccessful sweep for British warships.[7]

She next took part in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga in August 1915. A significant detachment from the High Seas Fleet, including eight dreadnoughts and three battlecruisers, went into the Baltic to clear the Gulf of Riga of Russian naval forces.[8] Pillau was initially assigned to the screening force that patrolled to the north of the gulf to prevent Russian forces from intervening in the operation. On 12 August, Pillau bombarded the Russian position at Zerel.[7] The following day, Russian submarines fired three torpedoes at the ship, all of which missed.[9] Pillau participated in the second attack on 16 August, led by the dreadnoughts Nassau and Posen. The minesweepers cleared the Russian minefields by the 20th, allowing the German squadron to enter the Gulf. On 25 August, Pillau bombarded Dagerort, destroying a lighthouse at St. Andreasburg and a coast watch station at Cape Ristna. The Russians had by this time withdrawn to Moon Sound, and the threat of Russian submarines and mines in the Gulf prompted the Germans to retreat. The major units of the High Seas Fleet were back in the North Sea before the end of August, Pillau arriving there on 29 August.[7][10]

Pillau resumed the series of patrols and minelaying operations in the North Sea for the rest of 1915. These included laying a minefield off Swarte Bank on 11–12 September and a sweep for British ships off the Amrun Bank on 19–20 October. A patrol in the German Bight followed on 23–24 October. All of these actions concluded without encountering British vessels. On 16 December, she and the rest of II Scouting Group swept through the Skagerrak and Kattegat in an attempt to locate British merchant shipping to Scandinavia, which ended on 18 December without significant success.[7]

The year 1916 began with a similar pattern, though from 6 to 11 February, the commander of the fleet's torpedo-boats, Kommodore (Commodore) Johannes Hartog, temporarily used Pillau as his flagship. During this period, Pillau led a patrol by the II, VII, and IX Torpedo-boat Flotillas to the western North Sea, which ended without combat. She participated in another fleet sweep on 5–6 March, followed by a patrol for II Scouting Group on 25–26 March. On 21 April, Pillau joined a patrol led by the battlecruisers of I Scouting Group toward Horns Rev that ended the next day, again having failed to locate any hostile warships. The flagship of II Scouting Group, the cruiser Graudenz, struck a mine during the operation; the acting commander, Kommodore Ludwig von Reuter, transferred to Pillau for the rest of the patrol. After arriving back at the naval base in Wilhelmshaven, Reuter transferred to the cruiser Regensburg. On 23–24 April, she participated in the bombardment of Yarmouth and Lowestoft in company with I Scouting Group. The cruisers of II Scouting Group briefly fought the British Harwich Force, but after the battlecruisers returned from bombarding Lowestoft, their gunfire dissuaded Rear Admiral Reginald Tyrwhitt from pursuit; the British quickly turned south and fled. The German ships arrived back in port on 25 April. She took part in another sweep toward the Amrun Bank on 4–5 May.[7][11]

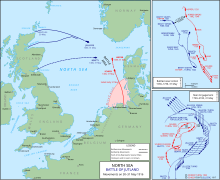

Battle of Jutland

In May 1916, Admiral Reinhard Scheer, the fleet commander, planned to lure a portion of the British fleet away from its bases and destroy it with the entire High Seas Fleet. Pillau remained in II Scouting Group, attached to I Scouting Group, for the operation. The squadron left the Jade roadstead at 02:00 on 31 May, bound for the waters of the Skagerrak. The main body of the fleet followed an hour and a half later.[12] Shortly before 15:30, the opposing cruiser screens engaged; Elbing was the first German cruiser to encounter the British. Pillau and Frankfurt steamed to assist, and at 16:12 they began firing on HMS Galatea and Phaeton at a range of 16,300 yards (14,900 m). As the British ships turned away, the German shells fell short, and at 16:17, Pillau and Frankfurt checked their fire.[13] About fifteen minutes later, the three cruisers engaged a seaplane launched by the seaplane tender HMS Engadine. They failed to score any hits, but the aircraft was forced off after which its engine broke down and it was forced to land. The three cruisers then returned to their stations ahead of the German battlecruisers.[14]

Shortly before 17:00, the British 5th Battle Squadron had arrived on the scene, and at 16:50 they spotted Pillau, Elbing, and Frankfurt. Eight minutes later, the powerful battleships HMS Warspite and Valiant opened fire at Pillau at a range of 17,000 yards (16,000 m). Several salvos fell close to the German cruisers, prompting them to lay a cloud of smoke and turn away at high speed. About an hour later, the German battlecruisers were attacked by the destroyers Onslow and Moresby, but Pillau, Frankfurt, and the battlecruisers' secondary guns drove them off.[15] At around 18:30, Pillau and the rest of II Scouting Group encountered the cruiser HMS Chester; they opened fire and scored several hits on the ship. As both sides' cruisers disengaged, Rear Admiral Horace Hood's three battlecruisers intervened. His flagship HMS Invincible scored a hit on Wiesbaden that exploded in her engine room and disabled the ship.[16] Pillau was also hit by a 12 in (305 mm) shell from HMS Inflexible. The shell exploded below the ship's chart house; most of the blast went overboard, but the starboard air supply shaft vented part of the explosion into the second boiler room. All six of the ship's coal-fired boilers were temporarily disabled, though she could still make 24 kn (44 km/h; 28 mph) on her four oil-fired boilers, allowing her to escape under cover of heavy fog. By 20:30, three of the six boilers were back in operation, allowing her to steam at 26 kn (48 km/h; 30 mph).[17]

At around 21:20, II Scouting Group again encountered the British battlecruisers. As they turned away, Pillau briefly came under fire from the battlecruisers, though to no effect. HMS Lion and Tiger both fired salvos at the ship before turning their attention to the battlecruiser SMS Derfflinger; Pillau's official record states that the British shooting was very inaccurate. Pillau and Frankfurt spotted the cruiser Castor and several destroyers shortly before 23:00. They each fired a torpedo at the British cruiser before turning back toward the German line without using their searchlights or guns to avoid drawing the British toward the German battleships.[18] By 04:00 on 1 June, the German fleet had evaded the British fleet and reached Horns Rev.[19] At 09:30, Pillau was detached from the fleet to assist the crippled battlecruiser Seydlitz, which was having trouble navigating back to port. Pillau steamed ahead of Seydlitz to guide her back to Wilhelmshaven, but shortly after 10:00, the battlecruiser ran aground off Sylt. After freeing Seydlitz at 10:30, the voyage back resumed, with a division of minesweepers steaming ahead testing the depth to prevent another grounding. Seydlitz continued to take on water and sink lower in the water; she turned around and steamed in reverse in an attempt to improve the situation. Pillau also attempted to tow the battlecruiser, but was unable because the line repeatedly snapped. A pair of pumping steamers arrived in the evening, and slow progress was made through the night, with Pillau still guiding the voyage. The ships reached the outer Jade lightship at 08:30 and anchored twenty minutes later. In the course of the engagement, Pillau had fired 113 rounds of 15 cm ammunition and four 8.8 cm shells. She also launched one torpedo. Her crew suffered four men killed and twenty-three wounded.[20]

Later service

Repairs to the ship were carried out at the AG Weser shipyard in Gröpelingen from 4 June to 18 July. She next went to sea on 18 August for a major fleet operation. The raid resulted in the action of 19 August 1916, an inconclusive clash that left several ships on both sides damaged or sunk by submarines, but no direct fleet encounter. Pillau saw no action during the operation, which concluded two days later. The ship next participated in a patrol with the rest of II Scouting Group in the direction of Terschelling on 25–26 September. Another fleet sweep toward the Dogger Bank took place on 18–20 October.[7][21] The operation led to a brief action on 19 October, an inconclusive sweep during which a British submarine torpedoed the cruiser München. The failure of the operation (coupled with the action of 19 August) convinced the German naval command to abandon its aggressive fleet strategy.[22] On 5 November, Pillau sortied as part of the covering force, along with I and II Scouting Groups and III Battle Squadron for the rescue of the crew of the U-boat U-20, which had run aground on the Danish coast.[23]

The year 1917 saw the ship largely confined to local defensive patrols in the German Bight, with little activity of note.[24] In July, a series of mutinies occurred on several ships of the fleet, including Pillau. While the ship was in harbor in Wilhelmshaven on the 20th, a group of 137 men left the ship to protest a cancellation of their leave. After a couple of hours in the town, the men returned to the ship and began to complete the tasks they had been ordered to do that morning as a show of good will. Pillau's commander did not take the event seriously, and ordered a limited punishment for the crewmen who had staged the protest.[25] By late 1917, Pillau had been assigned to IV Scouting Group, along with Stralsund and Regensburg. In October 1917, Pillau was dry docked for periodic maintenance, which was completed on 29 October.[24] Late that month, IV Scouting Group steamed to Pillau, arriving on the 30th. They were tasked with replacing the heavy units of the fleet that had just completed Operation Albion, the conquest of the islands in the Gulf of Riga, along with the battleships of the I Battle Squadron. The risk of mines that had come loose in a recent storm, however, prompted the naval command to cancel the mission, and Pillau and the rest of IV Scouting Group was ordered to return to the North Sea on 31 October.[26]

Upon returning the North Sea, Pillau returned to II Scouting Group. On 17 November, the four cruisers of II Scouting Group, supported by the battleships Kaiser and Kaiserin, covered a minesweeping operation in the North Sea. They were attacked by British cruisers, supported by battlecruisers and battleships, in the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight. Königsberg, II Scouting Group flagship, was damaged in the engagement, but the four cruisers managed to pull away from the British, drawing them toward the German dreadnoughts. They in turn forced the British to break off the attack; neither side had significant success in the operation.[27] Pillau was uner repair from 18 to 30 November at the Kaiserliche Werft (Imperial Shipyard) in Wilhelmshaven for the damage inflicted during the battle. She lost three men killed and another five wounded in the action.[24]

In April 1918, FK Adolf Pfeiffer took command of the ship.[28] On 23–24 April, the ship participated in an abortive fleet operation to attack British convoys to Norway. I Scouting Group and II Scouting Group, along with the Second Torpedo-Boat Flotilla were to attack a heavily guarded British convoy to Norway, with the rest of the High Seas Fleet steaming in support. The Germans failed to locate the convoy, which had in fact sailed the day before the fleet left port. As a result, Scheer broke off the operation and returned to port.[29] Pillau next took part in a minelaying operation with the rest of II Scouting Group in May. The cruisers conducted another patrol in the German Bight on 19 June. The ships laid another minefield over the course of 21–23 August. Pillau went to sea for what would be her last wartime operation on 30 September for a patrol in the North Sea. During the operation, the cruiser Frankfurt suffered damage to her starboard screw, so FK Hans Quaet-Faslem, the deputy commander of torpedo-boats, transferred his flag to Pillau for the rest of the patrol. The ships returned to port on 1 October without further incident.[24]

In October 1918, Pillau and the rest of II Scouting Group were to lead a final attack on the British navy. Pillau, Cöln, Dresden, and Königsberg were to attack merchant shipping in the Thames estuary while Karlsruhe, Nürnberg, and Graudenz were to bombard targets in Flanders, to draw out the British Grand Fleet.[30] Admirals Scheer and Franz von Hipper intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to secure a better bargaining position for Germany, whatever the cost to the fleet. On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on Thüringen and then on several other battleships mutinied. The unrest ultimately forced Hipper and Scheer to cancel the operation.[31] After the end of the war on 11 November, Pillau was not included on the list of ships to be interned at Scapa Flow, so she remained behind in Wilhelmshaven with a skeleton crew. On 31 March 1919, the ship was decommissioned. After the interned ships were scuttled by their crews in June, the Allies demanded Pillau and several other ships as replacement war prizes under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles.[24][32]

Italian service

She was stricken on 5 November 1919, and on 14 June 1920, she sailed from Germany in company with the cruisers Königsberg, Stralsund, and Strassburg and four torpedo-boats. They arrived in Cherbourg, France, over the course of 19–20 July, and they were surrendered to the Allies on the 20th. She was ceded to Italy as a war prize under the name "U".[33][34] She was renamed Bari and commissioned into the Regia Marina on 21 January 1924, initially classed as a scout.[35] The 8.8 cm anti-aircraft guns were replaced with 76 mm (3 in) /40 guns,[36] but she was otherwise little-altered from her German configuration.[37] In August 1925, Bari ran aground off Palermo, Sicily; she was refloated on 20 September.[38] On 19 July 1929, Bari was reclassified as a cruiser.[36] Bari joined the other two ex-German cruisers, Ancona and Taranto and the ex-German destroyer Premuda as the Scout Division of the 1st Squadron, based in La Spezia.[39]

Bari was modified slightly in the early 1930s, with a temporary extension to the bridge and her forward funnel was shortened to match the others.[40] In 1933–1934, she was refitted for colonial service and converted to oil-firing.[41] The six coal-fired boilers were removed to allow for additional oil bunker space, and the forward funnel was removed and the remaining two were cut down. This reduced her power to 21,000 shaft horsepower (16,000 kW) and a top speed of 24.5 kn (45.4 km/h; 28.2 mph). Her cruising range was increased considerably, from 2,600 nmi (4,800 km; 3,000 mi) at 14 kn (26 km/h; 16 mph) to 4,000 nmi (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at that speed.[36][35] After returning to service in September, Bari was sent on a deployment to the Red Sea, based in Italian East Africa. She remained there until May 1938, when she was relieved by the new sloop Eritrea, allowing her to return to Italy. During her deployment to the Red Sea, she was joined by Taranto in 1935.[35][40]

World War II

By the outbreak of World War II in September 1939, her armament had been increased by six 20 mm (0.79 in) guns and six 13.2 mm (0.52 in) machine guns.[36] She was activated for combat duty in 1940, when she became the flagship of the Forza Navale Speciale (Special Naval Force) during the Greco-Italian War. She supported the invasion of the island of Cephalonia and later shelled Greek positions in mainland Greece. Following the German intervention in April 1941 and Greece's defeat, Bari was tasked with escorting convoys from Italy to occupied Greek ports.[35] In the meantime, Italy had entered the wider World War in June 1940. In 1942, Italy planned to invade the island of Malta, and Bari and Taranto were to lead the landing force, but the operation was called off. In November that year, she served as the flagship of the amphibious force that landed at Bastia in Corsica. She took part in anti-partisan bombardments off the Montenegrin coast later that year.[40][41] That year, she was based in Livorno, where she was placed in reserve in January 1943.[35]

In early 1943, she was slated for conversion to an anti-aircraft ship. She was to be rearmed with six 90 mm (3.5 in) /50 guns, eight 37 mm (1.5 in) guns, and eight new model 20 mm /65 or /70 machine guns. The work would have required significant resources, and work had not yet begun by 28 June, when American bombers badly damaged Bari at Livorno and she sank in shallow water two days later.[35][36] At the Italian armistice in September 1943, she was further damaged to render her useless to the German occupiers.[41] The wreck was partially scrapped by the Germans in 1944. She was officially removed from the navy list on 27 February 1947, and raised on 13 January 1948 for scrapping.[36]

Footnotes

- ^ Dodson & Nottelmann, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b Gröner, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 161.

- ^ Gröner, p. 110.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Dodson & Nottelmann, p. 282.

- ^ a b c d e f Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 228.

- ^ Halpern, p. 197.

- ^ Polmar & Noot, p. 43.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 52–54.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 62.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Tarrant, p. 80.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 43–45, 100.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 112–113, 201.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 251, 253, 279.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Campbell, pp. 330–333, 341, 360, 403.

- ^ Massie, pp. 683–684.

- ^ Massie, p. 684.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 228–229.

- ^ a b c d e Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 229.

- ^ Woodward, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Staff, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Woodward, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 227.

- ^ Halpern, pp. 418–419.

- ^ Woodward, p. 116.

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 280–282.

- ^ Dodson & Cant, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Gröner, p. 111.

- ^ Dodson & Cant, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f Brescia, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d e f Fraccaroli, p. 265.

- ^ Dodson & Cant, p. 62.

- ^ "Telegrams in Brief". The Times. No. 44074. London. 22 September 1925. col G, p. 13.

- ^ Dodson, p. 153.

- ^ a b c Dodson, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Whitley, pp. 156–157.

References

- Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini's Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regia Marina 1930–1945. Barnsley: Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-84832-115-1.

- Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-1-55821-759-1.

- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Dodson, Aidan (2017). "After the Kaiser: The Imperial German Navy's Light Cruisers after 1918". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2017. London: Conway. pp. 140–159. ISBN 978-1-8448-6472-0.

- Dodson, Aidan; Nottelmann, Dirk (2021). The Kaiser's Cruisers 1871–1918. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-68247-745-8.

- Fraccaroli, Aldo (1986). "Italy". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 252–290. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 6. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0237-4.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York City: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-40878-5.

- Polmar, Norman & Noot, Jurrien (1991). Submarines of the Russian and Soviet Navies, 1718–1990. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-570-4.

- Staff, Gary (2008). Battle for the Baltic Islands. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84415-787-7.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-304-35848-9.

- Whitley, M. J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 1-85409-225-1.

- Woodward, David (1973). The Collapse of Power: Mutiny in the High Seas Fleet. London: Arthur Barker Ltd. ISBN 978-0-213-16431-7.

Further reading

- Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5267-4198-1.

External links

- Bari Marina Militare website

- v

- t

- e

Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine- Pillau (ex-Maraviev Amurskyy)

- Elbing (ex-Admiral Nevelskoy)

Regia Marina

Regia Marina- Bari (ex-Pillau)

Imperial Russian Navy

Imperial Russian Navy- Maraviev Amurskyy

- Admiral Nevelskoy

- Preceded by: Graudenz class

- Followed by: Wiesbaden class